Upaya is proud to announce that it has come together with 3rd Creek Foundation (3CF) to provide a follow-on investment into Maitri Livelihood Services Private Limited (Maitri), a caregivers training and placement company that recruits, trains, and secures employment for women from vulnerable backgrounds in the East and Northeast communities of India.

Upaya's Sreejith Nedumpully profiled on thealternative.in

As part of its coverage of the Deshpande Foundation's Development Dialogue 2015 in Hubli, thealternative.in sat down with Upaya's Director, Business Development Sreejith Nedumpully to talk about his previous work with Rope International, what initially drew him to Upaya, and where he sees the future of livelihood development in India.

The interview has been reprinted below with the permission of thealternative.in, while the original article can be found here.

Sreejith Nedumpully

In his role as Director (Business Development) at Upaya Social Ventures, Sreejith Nedumpully is enjoying the opportunity to realise his long time passion—building regional eco-systems of small enterprises with big impacts. As the co-founder and former Managing Director of Rope International, a manufacturer and supplier of handmade and handloom woven natural products, Sreejith has had over two decades of expertise in the domain of rural livelihoods and the challenges of scaling small businesses.

At the 8th annual Development Dialogue 2015, organised by the Deshpande Foundation in Hubli, The Alternative spoke to Sreejith about his journey from working with rural artisans to funding impact creating enterprises and the role of small businesses in making big change.

You have been involved in rural livelihood generation for over a decade. What are some of the chief learnings that led you to co-found Rope International?

During my work with in microfinance with DHAN Foundation in 2002, I got first hand exposure to the enterprising nature of people in rural India and how access to finance – by generating livelihoods – is directly linked to increased rural incomes. Thus, creating opportunities for gainful employment of BOP populations, besides permitting access to finance, can also permit a regular income stream to support a better standard of living. It also became evident that raising rural incomes was key to ensuring the financial inclusion of BOP populations.

At that time, in the midst of the discussion about capturing BOP markets through appropriate technology and customised product design, I found myself siding with those who were looking at reversing this trend by facilitating rural to urban transactions. So, we started focusing on livelihood generation by tying up with companies to outsource a part of their production to rural areas by setting up manufacturing centres in villages, employing and skilling rural manpower especially women’s groups, and supplying raw material to them.

This enabled companies that wished to increase production but, due to lack of physical infrastructure from working at full capacity, were unable to employ more people on site. This outsourced manufacturing model built the capacities of rural people and absorbed them into year-round employment.

Did you see this this creating an entrepreneurial mindset among these people?

It definitely did lead to the development of leadership qualities and better negotiating skills among the women employed in these units. Microfinance activities in the village had already empowered SHG women economically to some extent, making them confident and adept at negotiating with bankers for favourable financial deals. Further, under the outsourced manufacturing model, each unit was put under the leadership of 2-3 women who were responsible for managing finances and operations and that really honed their leadership qualities. Witnessing this transformation fired my own entrepreneurial ambitions.

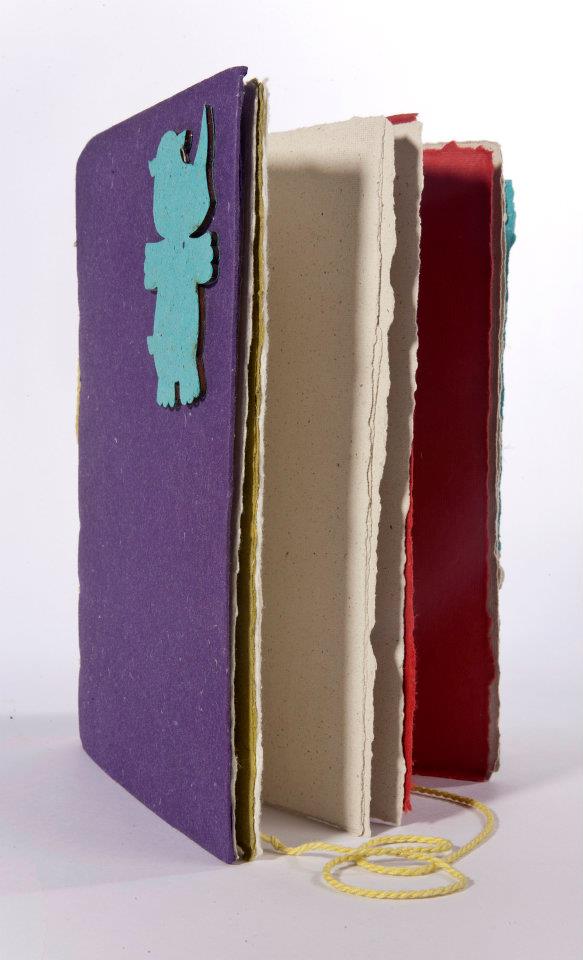

Rope provides global customers access to lifestyle products and home decor made by rural workers and artisans in India using natural fibres. Pic Courtesy – design21sdn.com

Was this then the beginning of Rope’s journey?

Yes, my initial idea was an extension of the outsourced manufacturing model – outsourcing both production and services to rural areas. With my idea incubated by IIT Madras, I was able to work on the upcoming rural BPO model while simultaneously building my own business plan for the rural manufacturing model.

In 2008, with seed funding from the IIT Madras incubator, we were able to launch Rope (now Rope International) with the aim of creating employment opportunities for rural artisans, many of whom were still employing age-old manufacturing techniques to create produce traditional designs. Many artisans had been left unemployed when demand for their crafts gradually disappeared.

We began Rope using a key account model – partnering with large brands like IKEA and Walmart with a large and steady demand for products with certain design specifications. By establishing rural manufacturing centres that met the supply requirements of these large clients, we were able to leverage the natural skill and traditional craft knowledge of the rural artisans, upskilling them in the process by introducing them to contemporary design ideas. The large volumes (sometimes 10 lakh pieces of a particular product) required by these brands helped us move beyond the level of handicrafts to a handmade production factory, with production flows, quality control mechanisms etc. all established within the village.

The work of Rope, initially centred around weaver clusters in Madurai began to expand to other districts Tamil Nadu, where we trained and employed a few hundred people. As we got buyers from India and overseas, the quantum of production too began to grow. That’s how Rope began to be successful.

What were some key lessons about scale that you learnt through Rope?

With Rope, the idea was to create rural employment opportunities at scale, providing alternative livelihoods to people formerly employed, often as bonded labour in the textile mills and firecracker product units in Tamil Nadu. Our model involved setting up a unit within the village which employs about 50-100 women and replicate those units in neighboring villages. So in two years, we had six such units, each directly employing 60-70 women.

Besides this, each unit also indirectly employed about 30-40 women from the village who would take work home, supply at their own convenience rather than contributing to core production. By 2010, we had established 6 such clusters of units. Besides production units, there was a central hubs that procured and supplied raw material as well as collected ready products from the units, they were places where quality care, packaging, and despatch took place. Thus, we managed to successfully create the best of village level production by shift a large part of the value chain to the rural areas.

Rope is now continuing to produce quality products in large volumes, creating rural livelihood opportunities, generating profit, and maintaining stable business with our key account customers.

Tamul Plates, an Assam based manufacturer of disposable palm leaf tableware is among Upaya’s portfolio companies. Pic Courtesy – dealcurry.com

In 2013, you shifted gears, moving to Upaya Social Ventures. What motivated this decision?

By 2013, Rope had achieved a degree of stability and production was going steady without the need for new marketing. I began getting restless, looking to create newer, more exciting growth models that weren’t dependent on scaling through the establishment and replication of manufacturing units. My own experience showed that Indian government laws were prohibitive, making it especially difficult to access capital, thereby limiting the scale that a manufacturing enterprise can achieve, especially in the case of handmade products.

I have always been interested in working with rural entrepreneurs, helping them develop their business ideas, shape their models, and scale. Upaya gave me the opportunity I was looking for.

Can you tell us about Upaya’s work with early stage rural entrepreneurs and the gap that it is trying to fill?

India is capital-starved country with a big gap in accessing early stage funding, even in the impact investing space, where investors look for proven, profitable business models,, and look to minimise risk with smaller investment sizes. The focus usually, in the investment space, is more on profit and less on impact.

Upaya Social Ventures’ LiftUp Project bridges this gap by providing early stage, for-profit entrepreneurs with seed financing and business development support to help them launch and scale their business. As the first institutional investor, Upaya puts in an equity investment of Rs. 20-30 lakhs in each of these enterprises with proven business models and a revenue of about Rs. 10-20 lakhs. Investments are structured over a 3-8 year timeline, during which an enterprise can scale, attract follow-up capital and become profitable. We handhold entrepreneurs for a 24-36 month period, providing them with technical assistance, financial management, and developing effective market strategies.

We also provide advisory support and help them understand their beneficiaries better with annual surveys profiling potential customers. Working with entrepreneurs to collect and analyse social data on employees to monitor their progress out of extreme poverty.

What kind of enterprises does Upaya support?

We specifically target entrepreneurs, rural and urban, with long-term vision and a strong business plan. Our main focus is on strong business models that create jobs for the poor, ensure a secure income source, and improve their quality of life. While scalability is important to us, it alone will not determine whether we invest in a company or not. We examine the geographical limitations of SMEs, market crowdedness, product relevance, and employment generation before investing in them. At present, Upaya is supporting 6 SMEs across 4 Indian states working in areas ranging from handcrafted paper to urban sanitation. The challenge is in finding and identifying good entrepreneurs in remote regions, often not exposed to networking platforms like conferences.

Upaya’s business incubation support to local providers of essential services enables large scale job creation for the urban poor. Pic Courtesy - Samagra Sanitation

How has Upaya gone about building an entrepreneurial eco-system for its portfolio companies?

Our focus right now is on supporting groups of ventures from a particular region, for example, in the north eastern states. This helps create a favourable eco-system that will attract other capital and service providers there, giving these entrepreneurs wider networks to tap into. For us, it is always more viable to enter a region where we can partner with other service providers.

MFIs, like MicroGraam, for example, which provide small entrepreneurial loans will help meet the SME’s working capital costs to fulfil existing demands, enabling them to use Upaya’s funds for further growth and expansion.

How does Upaya access finance to meet its capital requirements?

With early stage funding, we found that charity is relevant since donors are not looking for a quick exit from the venture, more patient with the capital deployed and reconciled with reaping lower returns (about 5-6%) than commercial and impact investors. So, Upaya, which is registered as a not-for-profit company in the US, raises philanthropic capital from family foundations and big donor agencies based in the US where interest in making recyclable capital deployments to sustainable and impactful social enterprises is on the rise.

What have been some of important learnings for you from this year’s Development Dialogue?

Given Upaya’s own focus on developing regional eco-systems that promote entrepreneurship, I find Deshpande Foundation’s regional hubs model very interesting. The sandbox model, by supporting budding entrepreneurs with access to capital, mentoring, etc., is creating an eco-system that can encourage the entrepreneurial spirit in the region. It is also enabling small enterprises to scale by inspiring and supporting replication in other places. It is important, while doing this, not to adopt a one-size-fits-all approach but to have business models that are customised to regional contexts, are specific to local needs, and that concentrate resources in smaller geographical areas. Thus, factoring scale into the model allows entrepreneurs to come on board irrespective of their size or reach, without scale serving as a barrier to entry.

While there are some models, like Akshaya Patra which have expanded across geographies, most enterprises are small and with application limited to the sandbox and being in the can be really beneficial to these small but profitable entrepreneurs working in niche areas who might not have pan-india scalability. The Hubli sandbox model, by providing support to these value creating enterprises has great relevance for the entrepreneurial needs of different parts of the country.

"Art to Mart" at the Deshpande Foundation’s Development Dialogue 2015

Following the Deshpande Foundation’s Development Dialogue 2015 conference in Hubli, thealternative.in published a series of session excerpts to share the learnings. I (Sreejith) had the chance to be a part of the "Art to Mart: How can we build an end-to-end value chain that brings artisans profitably to market?" panel.

The transcript of that session has been reprinted below as it appeared on thealternative.in. The original article can be found here.

With over six million people (officially) working with Handicrafts in India, traditional handicrafts are a major source of income for a large number of people in rural communities, and have a huge market potential, about 20,000 crore according to some estimates, across the globe.

But while the market itself seems to be thriving, the livelihoods for most of these artisans are not.Various factors – like wages, market price gaps, and lack of technology – are forcing these artisans to move away from the handicrafts industry, to more profitable work.

How does one create a sustainable, equitable value chain for these markets? How do we ensure that rural artisans – all artisans, for that matter – are able to reach the right markets without losing out on the profits due to them?

A panel discussion hosted by Sattva at the Development Dialogues 2015 brought together practitioners who work across the craft value chain in India,: Sreejith from Upaya Social Ventures and ROPE International; Neelam Maheshwari from Navodyami.org, and RangSutra‘s Sumita Ghose, moderated by Rathish Balakrishnan of Sattva.

Edited excerpts from the discussion:

Can market led solutions bring about equitable development?

Sumita: If we are talking about an equitable model of development, it is possible only in an organisation owned collectively by all, which is why RangSutra is a company owned by these artisans. It gives you a say in how the company is run, your wages etc. Earlier, a lot of the women we worked with were paid a pittance while working for middlemen, being paid per piece.

Now, they are paid properly, according to the material, skill and time inputs required. Having shares in the company gives them not just a right but also a responsibility. They ensure that the work is quality work because they know that the company’s profit decides their dividends.

The idea that your work is valuable, that there are people who are going to buy it and that you can make profit out of it gives them a power, an awareness of the value of your work, and that comes with equitable ownership. Using your own money makes a difference because it’s something you believe in, versus just doing something out of program funds.

An incident that really motivated me is when I visited this woman’s house in a village and she had framed a share certificate we had given her. She said it was the only property that I own, the land and the house are owned by my husband’s family. She was so proud.

Should the producer/community facing entity be different from the market-facing entity?

Sumita: We decided in the formation of RangSutra not to have many organizations, we don’t have one community facing and another market facing, that’s too complicated!

What these artisans do need are quality inputs, access to markets, efficiency, timing, delivery response etc. That remains a challenge especially in our case, where 95% of the artisans we work with are from villages.

Sreejith: A very important thing is for artisans to produce what sells, to keep updating what he makes. Can we find alternatives to the saree that a weaver can make if the saree market is going down? It’s possible. Like with artisans making mats for sleeping etc.. that market has completely vanished, nobody uses them anymore. A few players including Industree started making table mats or runners with the same material, a lot of these artisans were able to come back to their profession.

Sreejith: I completely agree that we should have a model that combines the equitable value distribution of community owned model with the efficiency of the dynamism of a private enterprise. But if I had to choose one, I’d choose market focused, more dynamic and efficient model for the question of sustainability.

Let me tell you an example which inspired me to entrepreneurship: In 2005, in Thanjavur, I visited some of the weavers’ cooperative societies that started with the best of intentions but were not working very well. We went to procure some sarees and find market for it to give an assured market to weavers. The cooperative societies complained that they had a huge stock of unsold sarees and therefore were unable to procure more from weavers. The weavers said that 90% of the weavers had migrated to cities to look for other jobs, so they had very little skilled labour.

They told me that someone had visited them from Holland, and was stunned by the beauty of these pieces but he asked them to make scarves or shawls as there was no market for sarees in Holland. But back then, there was no internet or any way of getting in touch with the market(or that man) and they got in the same rut of producing sarees in cooperative societies. The weavers told me they don’t want to weave sarees if there is market for it, they are glad to make anything else if it’s sold.

If that type of market dynamism were possible in a community led model, it would be great. But it’s not. Another reason is the shortage of capital.

I think for these reasons, the sustainability of the enterprise depends on their ability to continuously engage the artisans, irrespective of the structure is.

We always look for scale. Would you say that a simpler model could scale better?

Sreejith: A simpler model is more accountable, more efficient etc but that depends upon the entrepreneur who runs it. Of course, you need to scale, scaling is great, but it is not easy. Just because it has worked for some organizations in some sector, it doesn’t mean it will for all. It takes investment in capacity building, in system and community owned structure to have a good organisation. In some cases, private entrepreneur can do it much more efficiently and they have access to capital.

Neelam: To think that in 60 years in India, we have had just one FabIndia.

We don’t have enough models, we should look at these people as beneficiaries, but also entrepreneurs. For me, it’s an information gap, we need to connect producers to market opportunities. There are so many artisans, we need many more models, we can’t stick with one or two models that we think are good.

Sumita: Today, there are also lots of people leaving the field, I have seen that it’s more for young men than women. For women, it’s convenient as it allows them to earn a livelihood while working from home, but sometimes with the men, it’s more profitable to work in a city in some other job.

Sreejith: In my experience, I’d say men too are interested… provided they have a sustained income from craft. It’s not that they want to preserve the art of anything, they really need a livelihood.

Which one is more relevant to artisans, the B2B or B2C model?

Sreejith: I think B2C is extremely relevant, but in my experience, it takes more capital and therefore for smaller entrepreneurs with less access to capital it’s a difficult ball game. Look at FabIndia, it’s a very successful B2C model, but it takes a lot of capital.

When I started my company (ROPE International) in 2007, I was attracted by B2B opportunities and therefore I’ll talk more about that. When we started out, we did a market research and we saw that the US had 60 or 70 retailers double the size of FabIndia. They said that India has beautiful artisanal products but they don’t source majorly from India as they had issues about production, organization, compliance to social norms and so on in India. So when I started ROPE, my challenge was to build a model where consistent large scale, quality production is possible.

Sumita: RangSutra’s overarching goal is sustainable livelihoods for artisans. So for us, B2C model wasn’t viable for us when we started out. It is more difficult in India, because people take hand-skills for granted, they don’t understand why they have to pay more. Globally there is much more respect (than India) for handmade, because most people in other parts of the world have lost that skill. We do have challenges given our goal, there have been situations where we have had to make an order and make no margin at all just so that an artisan can work.

The panel wrapped up with 2 important takeaways: Building sustainable livelihoods is the obviously the most important thing to keep artisans in their work. Produce what sells, be flexible.

This article is part of a series of panel discussions and reports from the Deshpande Foundation’s Development Dialogue 2015 conference in Hubli. The Development Dialogue is a conclave of like-minded people from across the country who believe in entrepreneurship as a way of nurturing scalable solutions for development, an International social entrepreneurship ecosystem conference hosted by Deshpande Foundation India.

Upaya Joins With Ennovent IIH, LAF: Creative Venture Fund to Expand Youth Employment and Employability Through Investment in Anant Learning & Development

Upaya is proud to announce today that it has come together with Ennovent Impact Investment Holding (Ennovent IIH) and LAF: Creative Venture Fund (LAF:CVF) to invest in Anant Learning & Development (Anant), a Delhi-based company that is working to ensure young people from poor communities across India have adequate skills training and regular access to secure stable employment with credible employers. Upaya will provide funding and business development support to Anant through its LiftUP Project framework.

Anant has developed a two-track model for improving labor markets for young people. First, the company provides placement and post-placement services through its Rozgarmela.com platform to youth in both urban and rural communities across India. Second, Anant consults with private and public sector employers to assess the effectiveness of their skill development programs through skills assessments and post-placement tracking. Anant currently operates in nine states [within India].

“Having overseen many vocational training projects in the past, I saw that the young men and women who graduated out of training programs quickly fell back out of the formal sector workforce,” said Anant Founder and CEO Ajit Singh.

“These young people often claimed frequent miscommunication of salary, benefits as well as job roles by training and placement agencies while, at the same time, employers complained of high attrition and need for credible intermediaries for sourcing candidates. The misalignment of incentives of training and placement agencies is a central issue, and I thought that a more transparent, data-driven approach could iron out the inefficiencies in the market,” said Singh.

Unlike many placement websites in India, Anant does not collect fees from the young people being placed. Instead, the company harnesses its data collection capabilities to provide actionable insights to employers, training agencies, and government agencies so that each can improve the efficacy and efficiency of their efforts.

Singh expects to enroll 10 employers every month on Rozgarmela.com, who are collectively projected to hire approximately 250 candidates.

The Ennovent Circle, an exclusive group that collaborates to accelerate innovations for low-income markets, facilitated the investment in Anant. Both Upaya and Ennovent IIH are Ennovent Circle members.

“The unique selling point of Anant is its strong linkages to the industry and direct contact with the beneficiaries. This helps the company understand the needs of the potential employees and connects the disconnected rural youth to the employment system,”said Ennovent Circle Manager Joel Rodrigues. “The Ennovent Impact Investment Holding is optimistic about the impact Anant will be able to create at the grass roots through this investment,” said Rodrigues.

Upaya’s support of Anant has been made possible by LAF:CVF, a venture philanthropy fund that invests in employment and empowerment initiatives that provide vulnerable youth around the world with the means to create a better life for themselves.

“Upaya sees Anant’s platform as enhancing the ability of young men and women from poor communities to earn a stable, dignified living,” said Upaya’s Director, Business Development Sreejith Nedumpully. “By harnessing technology along with a geographically diverse network of trainers and assessors, Anant is able to remove the inefficiencies from the system,” said Nedumpully.

Assam-Based Tamul Plates Receives Follow-On Investment from Artha Initiative & Upaya Social Ventures

Tamul Plates Marketing Pvt. Ltd. is announcing today that the company has come to an agreement with Artha Initiative and Upaya Social Ventures on an investment that will allow Northeast India’s leading producer of palm leaf tableware to significantly expand its operations across the region.

The deal is notable as Tamul Plates is the only established producer of disposable tableware in the Northeast - a region with more than 100,000 hectares of arecanut under plantation and one of the poorest areas of the country.

“This investment is a recognition that Tamul Plates is well positioned to meet the growing demand for high quality, environmentally responsible, and ethically produced products,” said Tamul Plates CEO Arindam Dasgupta. “Working in the Northeast, the company benefits from a unique combination of access to the highest quality raw materials and a producer base that takes great pride in its craftsmanship,” said Dasgupta.

Tamul Plates produces and markets high-quality, all-natural disposable plates and bowls made from arecanut (palm) tree leaves and sells them under the “Tambul Leaf Plates” brand. The company’s clientele includes a mix of restaurants, fast food establishments, event managers, and direct-to-consumer retailers.

This investment follows a recent agreement between Tamul Plates and the Government of Assam to supply the equipment for and train an extended network of affiliate rural producers. The investment by Artha and Upaya will allow the Barpeta-based company to make use of that expanded affiliate producer network by diversifying its product line, expanding its domestic sales and distribution networks, and opening export markets for its products.

“It has been a highlight of the Artha Venture Challenge to uncover a pioneering and innovative enterprise in Tamul Plates,” said Artha Initiative’s Director Audrey Selian. “We are particularly happy to be co-investing with Upaya, and look forward to continued efforts in collaboration sector-wide through our AVC and ArthaPlatform.com programming,” said Selian. Artha Initiative is associated with Switzerland-based Rianta Capital Zurich.

Disposable arecanut dinnerware is hygienic, chemical-free, compostable, microwave safe - and in high demand among urban consumers around the world. The production and sale of natural arecanut dinnerware not only reduces the deforestation and pollution associated with the production of traditional disposable dishes, but also provides a viable livelihood to disadvantaged communities.

“Upaya has been very impressed by the work of Arindam and his team over the past year, and believe that the company’s growth plans will benefit both customers and producers alike,” said Upaya’s Director, Business Development Sreejith Nedumpully. “We are proud to join the Artha Initiative in backing this promising enterprise, and are exciting about the company’s potential,” said Nedumpully. Upaya was Tamul Plates’s first investor.

This co-investment in Tamul Plates is the first deal completed under the formalized collaboration framework between Artha and Upaya that was announced in November 2014. Per that agreement, the two organizations are working together to deploy seed capital to help SGBs scale and create employment for the poor, share best practices around sound financial management, and disseminate tools and training for the benefit of India's wider ecosystem.

Drishtee, Upaya Come Together to Launch New Rural Supply Chain Social Venture

Upaya Social Ventures and Drishtee Development and Communications Ltd. are proud to announce a social venture collaboration that will create new opportunities for rural artisans to rely on their trade to earn a stable and dignified living. This pilot project with Drishtee will fill gaps in regional value chains by connecting groups of producers in rural communities across Assam, Bihar, and Uttar Pradesh with raw material suppliers and wholesale buyers of their products.

The pilot provides these groups - known as Community-Owned Enterprises (COEs) - with the technical training, management infrastructure, and market linkages needed for community-level entrepreneurship to thrive beyond their immediate area.

“In building Drishtee, we saw a new opportunity in organizing and formalizing the thousands of sole proprietors in or adjacent to our network,” said Drishtee Co-Founder and Managing Director Satyan Mishra. “Right now, village level producers are generally on their own. They are sole proprietors with very little reach outside their immediate area, and do not have the means or ability to develop customer relationships with larger clients for their product or service,” said Mishra.

Drishtee is a social enterprise that provides goods and services across rural India through locally owned village kiosk franchises. The kiosks provide services such as health, education, banking, microfinance, and livelihood services, as well as market linkages for independent farmers and other agri-processors. The Drishtee network currently serves the needs of over 14,000 rural households.

“This pilot with Drishtee - a successful company in its own right - is somewhat different from the typical business Upaya incubates through the LiftUP Project. However, the pilot’s ambitious and unique model provides an opportunity to secure stable, dignified livelihoods for small scale rural producers by connecting them with larger regional and national buyers,” said Upaya’s Director, Business Development Sreejith Nedumpully.

The initial pilot will focus on incubation of three to four COEs in the handloom textile and apparel production value chain. Per the initial plan, each of the prospective COEs will perform different steps in the process including thread spinning, weaving, sewing and garment finishing. Over the initial months of the pilot, Drishtee will organize and formalize the groups, provide training in design and quality control, and provide the necessary connections with wholesale customers. Each COE affiliated with Drishtee will employ at least 10 -15 people on a consistent basis.

“By building individual skills and allowing each person to focus on a piece of the production process, each participant can earn a living without fully bearing the burden of managing their own sole proprietorship” said Nedumpully.

At the time the company is launched, it will be lead by Vikas Mukundan, a Drishtee veteran who was selected to head up the new project. Throughout the process, Vikas will be supported by Mishra as well as members of the Upaya team.

As the pilot reaches its one-year mark, Upaya and Drishtee will review the progress toward the milestone goals and consider an expansion of the program.

Sreejith Nedumpully to Speak at IIMB Vista'14 "Entrepreneurship Conclave"

Upaya's Director, Business Development Sreejith Nedumpully has been invited to speak at the Indian Institute of Management Bangalore (IIMB) Vista '14 "Entrepreneurship Conclave." The event gives aspiring entrepreneurs an opportunity to speak with accomplished leaders in a conversational forum.

Sreejith will join reBus.in Co-Founder Phanindra Sama, BigBasket Co-founder Vipul Parekh, Bangalore Chapter of Mumbai Angels Head Veena Avadhanam, N.S.Raghavan Centre for Entrepreneurial Learning (NSRCEL) professor K Kumar, and filmmaker, author, and entrepreneur Varun Agarwal as speakers.

Vista'14 is IIMB's Annual International Business Summit and entrepreneurship competition. The Summit will be held in Bangalore September 26-28.

What We're Reading August 2014: Summer Breeze

Stanford Graduate School of Business “Does Impact Investing Really Have Impact?” (4 August 2014)

Jyotsna came across this YouTube video of a panel discussion on Impact Investing from the 2013 Social Innovation Summit at the Stanford Graduate School of Business. It led to a good debate around what the merit of impact investment really is, and whether or not it could become a mainstream asset class or another form of venture philanthropy.

Jyotsna also took pride in noting that Michael Smith from the White House Social Innovation Fund is exhorting exactly the type of evidence-based practice that Upaya holds central to its approach through continually measuring outcomes, refining models, and improving the business program to maximize benefit. He also warns of a trend he sees in investors who seek out innovation by “running after bright shiny objects and creating things people don’t need,” and instead is promoting efforts that are focused on measurably better, outsized positive effects for the public. We couldn’t agree more with this approach.

The Nand & Jeet Khemka Forum Podcast “Artha Initiative: Investing For Impact with Audrey Selian” (August 2014)

Sreejith sent around this great audio interview with Audrey Selian, Director of Rianta Capital’s Artha Challenge in which Audrey hits on some really interesting insights about impact investing. In particular, we felt her comments on sacrificing good investments in search of perfect investments were spot on. She also made some nice points on creating social value in areas where most infrastructure and services are non-existent. Definitely worth the read.

Stanford Social Innovation Review “Fundraising is Fundamental” (26 February 2014)

Laurel sent this piece around to the team in early August. She was struck by the way the authors touted the interesting correlation between forward thinking, innovative nonprofits and discomfort around fundraising.

“The organizations that have the most compelling logic models and the most impressive record of impact (as demonstrated by external impact evaluations) tend to be the worst at raising money—and vice versa ... At many bold and extraordinary nonprofits, people cease to be bold when the topic of fundraising comes up.”

The authors throw out a number of ideas for overcoming this "unfortunate inverse correlation." One strategy is approaching external actors as potential collaborators and passionate partners in the fight to end poverty, instead of as potential funders. This attitude can humanize all players and lead to deeper personal relationships. It also opens up an organization to support in a wider variety of forms - be it moral, in-kind, strategic or material. Of course, she noted that we at Upaya also accept snacks.

Catch Upaya Onstage at Sankalp Unconvention Summit 2014!

Upaya's Sreejith Nedumpully will join a panel of industry leaders to discuss the experience of supporting promising entrepreneurs in their earliest days.

Bridging the Pioneer Gap: Are We Meeting the Needs of Social Startups & What Can We Do Better?

11:45 AM - 1:15 PM, April 11 2014

Grand Ballroom A3

Hotel Renaissance, Powai, Mumbai

Over the past few years we have heard the conversation about the needs of businesses in the “Pioneer Gap“ reach a fever pitch – particularly in a frothy impact investment market that finds itself starving for more established, less risky opportunities. At the same time, a chorus of ambitious social entrepreneurs with promising models talks about finding themselves in a desert of funding and advisory support. The reality is that, if we rely on traditional venture capital models, most social investment funds will be financially unable to find, fund, and advise these companies in their infancy.

With the majority of these entrepreneurs exhausting their limited runways long before their transformative potential can be realized, there is a strong need to mobilize our peers and create an ecosystem for Pioneering Capital to fill the gap. The assembled panel will explore what’s working, what’s not, and what steps the sector can take to mobilize more resources for the next generation of effective social enterprises.

Moderator:

Ashish Karamchandani, Partner, Monitor Group

Speakers:

Sreejith Nedumpully, Director, Business Development Upaya Social Ventures

Harish Hande, MD, SELCO

Aditi Shrivastava, Head, Intellecap Impact Investment Network

Simon Desjardins, Programme Manager, Shell Foundation

Paul Breloff, Managing Director, Accion Venture Lab

Elrhino and Upaya Social Ventures Come Together to Create Jobs, Protect Wildlife in Assam

Upaya Social Ventures is proud to announce that it has begun work with Guwahati, Assam-based Elrhino, a promising venture with an unlikely product - handcrafted luxury paper, stationery products, and packaging materials made from recycled rhinoceros and elephant dung and other natural waste. The company will receive seed capital and ongoing business development support from Upaya through the latter’s LiftUP Project framework.

Elrhino manages the entire dung paper production chain including collection, preparation, processing, and sale of finished dung paper goods. The company is led by Nisha Bora, a young Assam native who is building on the work begun by her father over three years ago to create new livelihoods and increase the value of rhinoceros and elephants to local villagers. In the two years since its creation, Elrhino has made its mark in the Indian market as well as in France, and has created significant brand equity.

“We started Elrhino because we wanted to see Assam and its rhinos thrive,” said Elrhino CEO Nisha Bora. “We are creating opportunities for people to earn a truly sustainable living, one that provides economic stability for families and encourages people to preserve the natural habitats of these great animals,” said Bora.

Elrhino sees opportunities to create jobs for and build the skills of people - in the rural areas around Guwahati and the reserve forests of Assam. With its current infrastructure, Elrhino has the capacity to produce 15 tonnes of paper per year, which at capacity will equate to approximately 100 full-time jobs in paper processing and an additional 500 part-time jobs through a combination of resource collection and value-add production.

“We are committed to creating rural livelihoods and a skilled workforce in Assam,” said Sreejith Nedumpully, Upaya’s Director, Business Development. “At Elrhino, people learn two skill sets: how to make paper, and how to convert paper into products. We are very excited by the job creation potential in both areas,” Nedumpully said.

While Elrhino is Upaya’s sixth overall investment and second partnership in Assam, Nisha Bora is the first female entrepreneur in Upaya’s LiftUP Project network.

“Trust is a critical element of building successful companies in ultra poor communities, and across our portfolio we have seen a unique trust dynamic emerge between female managers and the women who work for the company,” said Nedumpully. “While she is the first woman leader we’ve partnered with, she will certainly not be the last,” he said.

Upaya's Sreejith Nedumpully Joined By Several LiftUP Project Partners at 3rd Annual Action for India Forum

This January Upaya's Director, Business Development Sreejith Nedumpully travelled to Delhi to participate in the 3rd Annual Action for India forum. The two-day, invitation-only national conference brought together 100 leading social innovators with an equal number of donors, technology leaders, impact investors, and senior government officials.

At the event Sreejith was joined by many of Upaya's LiftUP Project partners including Dr. Ravi Chandra of Eco Kargha, Swapnil Chaturvedi of Samagra, and Ajaya Mohapatra of Justrojgar.

"The forum was a wonderful opportunity for Upaya to meet the best of India's emerging and established social entrepreneurs, and to introduce our current LiftUP Project partners to the country's leading supporters of social innovation," said Nedumpully.

This year's forum was headlined by leaders from across the spectrum of Indian innovation and industry including Mr. Sam Pitroda, Mr. Desh Deshpande, and Mr. R Chandrasekaran.

December Newsletter: 1,139 Jobs and Counting!

Today, I am proud to share Upaya’s latest milestone - as of this week, our five LiftUP Project partners are collectively employing over 1,100 people!

Combining the continued growth of our early partners with the addition of Samagra and Tamul Plates to our LiftUP Project, Upaya has seen the number of people employed by its partners more than double since the spring.

Click here to read Upaya's quarterly newsletter and learn more!

Upaya Transitions Out of its LiftUP Project Partnership with Justrojgar

Upaya has decided to wind down its LiftUP Project partnership with Delhi-based Justrojgar following a difference with management about operating practices. With this change, Upaya will continue to hold its equity position in the company, however, the Upaya team will no longer provide technical support that is central to its LiftUP Project partnerships.

“While we are altering the structure of our partnership with Justrojgar, we maintain our fundamental belief that the facilities management sector - both commercial and residential - represents a tremendous opportunity to create large-scale employment for ultra poor slumdwellers” said Upaya Director, Business Development Sreejith Nedumpully.

Sreejith Nedumpully Joins the Upaya Team as Director, Business Development

Upaya Social Ventures is proud to announce that Sreejith Nedumpully has joined the organization as Director, Business Development. In his role, Sreejith will lead Upaya’s LiftUP Project in India.

Sreejith brings to Upaya over 12 years of experience in retail, emerging markets, financial inclusion, SME promotion, incubation and entrepreneurship. Most recently, he was the Co-Founder and Managing Director of ROPE International, a premium brand of natural, handmade lifestyle products from renewable materials. Today the company creates employment opportunities for over 1,000 rural artisans through its village cluster model, and wholesales its products to a variety of well-recognized domestic and international retailers.

Throughout his career, Sreejith has been involved with several social enterprise efforts including work with TeNeT Group, IIT Madras, Villgro Innovations Foundation, and the DHAN Foundation, and has consulted for organizations including Business and Finance Consulting GmbH Zurich, Women on Wings, the Sir Ratan Tata Trust, and Simpa Networks.

Nedumpully’s arrival follows the spring departure of Upaya Co-Founder Sriram Gutta. Gutta was recently named a Fulbright scholar and is pursuing a Masters degree.